MBITI: Corruption purge exposes overnight millionaires in unexplained wealth suits

By Mwongela Mbiti

Many people outside the United Kingdom (UK) probably have never heard of Zamira Hajiyeva.

Zamira, whose husband was a former chairman of a state-controlled bank and imprisoned for fraud in their native country Azerbaijan, led a lavish lifestyle, spending an equivalent of Sh2 billion in Harrods over a decade.

The British authorities established that she also owned Sh1.5 billion house in Knightsbridge and a golf course in Berkshire with no known legitimate source of income and no history of tax remittances.

Having established that Zamira had no income sufficient to acquire the listed properties, the authorities sanctioned the Unexplained Wealth Order (UWO) with a view of forfeiting the assets without having to charge her in court for any particular offence relating to the acquisition of the properties.

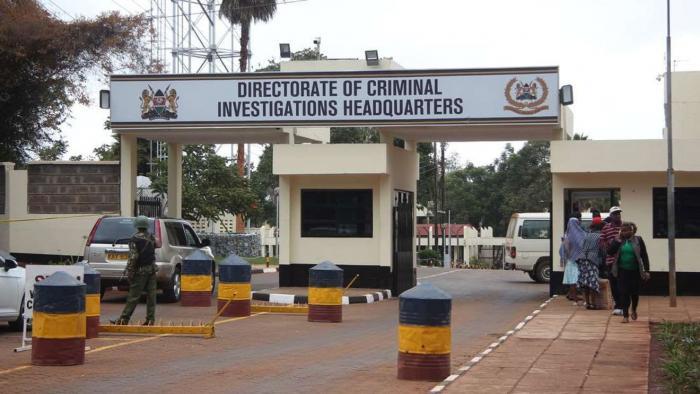

Kenya, just like the UK, has in place an equivalent of the Unexplained Wealth Orders.

In fact, the UK borrowed the concept from our own Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act enacted in 2003 as one of the innovative weapons and highly effective ways of denying the perpetrators the luxury of enjoying the proceeds of corruption.

A situational analysis and in view of recent court success in the forfeiture of unexplained assets shows that Kenya has one of the best collection of tools to conduct this drive.

In a country where, rather than shunning those who have made their wealth through illicit means, we celebrate them and where corruption has no stigma or social consequence Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission’s strategy of going for instant millionaires is a welcome relief likely to save a generation that has been cultured to get rich quickly at whatever cost.

Amuti case

The EACC has reported forfeiture of unexplained assets worth over Sh500m in the last two years after the breakthrough in what has come to be known as the ‘Amuti Case’ that engaged the Commission in a protracted court battle lasting over a decade.

Stanley Mombo Amuti was your typical civil servant who had 25 years of work experience in both private and public service.

In 2008, he was a financial controller with the National Water Conservation and Pipeline Corporation having risen through the ranks and earned a gross salary of Sh306,000 per month.

Beginning September 2007, Amuti was visited by benevolence and a long stretch of good luck that saw him make a cumulative bank deposit of Sh140,976,020.00 by June 2008.

EACC moved to court in 2008 seeking to forfeit both the cash and the landed properties on account that the same was acquired at or around a time when Amuti was suspected of engaging in corrupt conduct and that he could not explain its sources.

The court ordered Amuti to pay the government of Kenya Sh41,208,000 being an amount of money disproportionate to his know sources of income.

Innovative strategy

This case has since opened the doors for several others in what appears to be an innovative strategy and a tool for obtaining low hanging fruits in the fight against corruption.

With this strategy, the agency need not prove culpability for any corruption offence and the standard of proof is on a balance of probability as opposed to the requirement to prove beyond reasonable doubt in criminal prosecution.

It is required to satisfy the court that the assets were acquired at/or around the time the person was suspected of corrupt conduct, that the assets are disproportionate to that person’s known legitimate sources of income and having been granted an opportunity to explain, such explanation was unsatisfactory.

New targets

In the recent past, the agency has targeted these secret and instant millionaires including junior and senior county officers, members of county assemblies and other senior public officials who have amassed unexplainable wealth.

The axe has already fallen on several public officers in the last one year alone with the agency successfully forfeiting in the excess of Ksh. 400M from two cases and hundreds of millions worth of others pending in court.

Jimmy Kiamba

One of the cases that attracted a lot of media attention is that of Jimmy Mutuku Kiamba, a former Chief Officer Finance in Nairobi County during Dr. Evans Kidero’s administration.

Kiamba, who had previously worked with the defunct local authorities, is said to have transacted in over Sh1 billion between the year 2009 and 2015.

At the time of the suit, Kiamba was earning Ksh. 145,326/60 per month.

In this suit, EACC sought to forfeit Sh575,121,611 in form of cash and other properties registered in his name, that of his wife and children which in its opinion was unexplained.

Justice Ong’udi in July 2019, agreed with EACC that indeed Kiamba had in his possession unexplained assets and ordered him to pay the government Sh317, 648,604.

Thomas Njogu

The most recent casualty of the EACC’s graft purge is Thomas Njogu, early this year.

He was a senior Ministry of Interior officer earning a gross pay of Kshs. 155,000 but had managed to build over Sh100 million estate between January 2016 and August 2017.

Justice John Onyiego in his decree in favour of EACC ordered Njogu to surrender Sh48 million in cash and properties worth Sh67 million as he could not explain how he amassed the same within such a short period of time.

This non-conviction-based seizure and forfeiture of questionable assets is a very innovative strategy that promises quick wins by busting fraudsters and discouraging conduits who hold assets on behalf of thieving public officers.

Once again, disruption, in addition to prosecution, should be the strategy in fighting corruption.

Mwongela Mbiti is an advocate of the High Court of Kenya and a human rights activist