List of countries offering to help Kenya take on deadly gangs in Haiti

At least a dozen nations have told the United States that they will join the effort to help Haiti tackle the unchecked gang violence engulfing the country, pending a United Nations Security Council resolution authorizing a foreign intervention led by the government of Kenya.

The U.S., which along with Ecuador has authored a draft resolution for the Security Council, is expected to seek approval for it as early as this week after working behind the scenes to build support both among the council’s 15 members and in the wider international community.

The Miami Herald reports that for now, the Biden administration is remaining tight-lipped on which countries have pledged to provide support, saying only that as the lead nation, Kenya is expected to be the largest contributor with 1,000 police officers and troops.

But the Miami Herald has learned through several diplomatic sources which countries have stated a willingness so far to contribute to the mission, in the form of equipment, money or boots on the ground.

Besides The Bahamas, Jamaica and Antigua and Barbuda, which had previously announced their intent to take part in the mission, the others are Italy, Spain, Mongolia, Senegal, Belize, Suriname, Guatemala and Peru.

Spain’s Acting Foreign Minister, José Manuel Albares Bueno, publicly expressed his support last week, telling reporters in a press conference that his government, a previous financial supporter of Haiti, is waiting for the Security Council’s decision to determine the specifics of its assistance. The English-speaking Central American nation of Belize also expressed a similar sentiment during a meeting hosted by U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken on Friday on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly in New York. In a symbolic gesture, Belize offered to deploy up to 50 uniformed personnel to help the Multinational Security Support Mission.

But its participation, a source knowledgeable about the offer said, will depend on the U.N. resolution and on how the mission will be paid for. The decision on whether its personnel will be police or military, will be decided once the mission is defined.

Antigua, located in the Eastern Caribbean, also is waiting to decide on how many people it will deploy, while The Bahamas, which announced a deployment of 150 individuals in August, is also waiting for the U.N. vote to finalize its support.

“The Bahamas looks forward to working with Kenya and other partners in Haiti to assist in efforts to bring about peace and stability,” the foreign ministry said, while urging passage of the resolution by the Security Council.

Two other countries that are also looking at deploying boots on the ground are Suriname, the Dutch-speaking country in South America, and Rwanda, where French is an official language alongside English.

While Rwandan President Paul Kagame expressed his support for Haiti during a meeting of Caribbean leaders in Trinidad in July, his country was not among the 34 nations represented Friday around the table during the security meeting inside a ballroom at the Lotte New York Palace Hotel in Manhattan.

Kagame has faced mounting criticism over accusations that democracy is backsliding in his African nation due to his support for rebels in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo, treatment of journalists and arrests of critics. One of them was Paul Rusesabagina, whose heroic efforts to save some of the minority Tutsi population during the 1994 genocide inspired the film “Hotel Rwanda.” Rusesabagina’s high-profile 2020 arrest in Rwanda drew international condemnation and increased scrutiny by members of Congress, who will need to sign off on U.S. support for the Kenya-led mission.

One source said the African nation, which participated in the last U.N. peacekeeping mission in Haiti, has discussed sending up to 500 uniformed personnel.

“There were offers of support from Asia, Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean,” Assistant Secretary of State Brian Nichols said last week at a press conference, where he and Acting Deputy Secretary of State Victoria Nuland declined to name countries. “People were coming up to us … saying, ‘Hey, we’re in, we’re going to support; we are going to provide troops, we’re going to provide police, we’re going to provide money.’ ”

In recent weeks, the security situation in Haiti has rapidly deteriorated, with tens of thousands of Haitians forced out of their homes by armed gunmen, who control large swaths of the Haitian capital. Over the weekend, gunmen with the Canaan gang twice attacked the town of Saut-d’eau just north of Port-au-Prince.

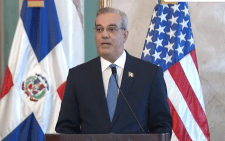

On Monday night, the same gang invaded the town of Mirebalais in the Central Plateau. The country’s largest medical facility, the University Hospital, was hit by a hail of bullets. In a speech to the U.N. last week, Haiti Prime Minister Ariel Henry said the recent attacks by armed gangs, which control at least 80% of the capital, had led to a new humanitarian crisis. Displaced Haitians are now occupying more than two dozen schools in metropolitan Port-au-Prince under “subhuman conditions.”

“We are not here to make up for or justify the past,” he said. “We are here to ask friendly countries to understand there is something urgent to be done to benefit the people of Haiti.”

Nearly a year after he first made the request for a multinational force, he reiterated the call for the Security Council to authorize the deployment of a mission to help bolster the Haiti National Police force. During the meeting on the escalating security crisis in Haiti, U.S. officials announced that the administration would work with Congress to secure $100 million in funding for the Kenya-led mission.

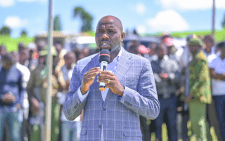

The Pentagon is also prepared to provide “robust enabling support,” the U.S. secretary of state said, including planning assistance, intelligence, airlifts, communications and medical support. On Monday, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Kenya’s Defense Minister Aden Duale signed a bilateral defense agreement in Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, paving the way for assistance. Kenya’s President, William Ruto, had said that in order for his country to commit to lead a security intervention to help Haiti’s police force disarm gangs, he would need, along with a Security Council resolution, at least 2,000 uniformed personnel. He also wants to see more support, especially from the region.

Latin American experts have said that given the ongoing crime challenges in many of the countries, governments cannot afford to spare law enforcement officers for what the U.S. has described as a police mission. Haiti observers have said that given the complexity of the country’s gang crisis and terrain, any security mission should consist of military personnel.

Kenya, which sent an assessment delegation to Port-au-Prince in August, is now looking at not just deploying members of its specialized border police unit, but also soldiers, a source familiar with the discussions told the Herald.

“There’s a range of how countries operate,” Nuland said. “There are a number of countries, including the Kenyans, that have high-end police…. So I think the majority you will see will be in that category. But there are countries that will want to contribute that only have military to offer. So it’ll be an integrated force.”

Nuland declined to discuss the proposed force’s strength, saying she will not get into the overall size, and once the resolution passes, the U.S. will work with the Kenyans on what their needs are and then make the rounds among nations.

“The Kenyans have not yet provided the full list of what they need, so that’s one of the reasons why people haven’t been able to define their contributions more specifically,” Nichols said. “The Kenyans have committed that they’re going to get their asks ready so that we can really inventory what the needs are and what people will bring to the table.”