Hepatitis scourge: Alarm as silent viral killer on the rise in Kenya

When John Ndichu noticed a persistent yellow colour in his eyes in 2016, he quickly dismissed it as the effect of intoxication.

At the time, he was undergoing methadone treatment to wean him off heroin, a drug he had been using for ten years.

However, the subsequent yellowing of his urine prompted him to seek medical advice.

He got tested at a methadone clinic in Dagoretti and was diagnosed with hepatitis C.

For the next few weeks, Ndichu visited the clinic daily to get treatment offered to people who inject drugs (PWID) for free.

“It was hard. The clinic did not allow me get the drugs and carry them home. Instead, I had to report to the facility every day to collect the tablets,” he recalls.

After completing his medication, he was tested again and the results showed that the infection had cleared.

Some of his friends, who were injecting drugs and had been diagnosed with Hepatitis C, were however not as lucky: they kept getting re-infected.

Key population

Ndichu is among a key population of PWIDs that accounts for the highest new infections of Hepatitis C, currently at 23 per cent of 1.75 million infections that occur every year globally.

Hepatitis, an inflammation of the liver caused by a virus, manifests in five ways: A, B, C, D and E, with different viruses responsible for each type.

Common symptoms are aching joints, yellow skin, loss of appetite, fatigue, dark urine, stomach pain and fever.

Some people do not show any symptoms at all, and when they do, it is usually too late.

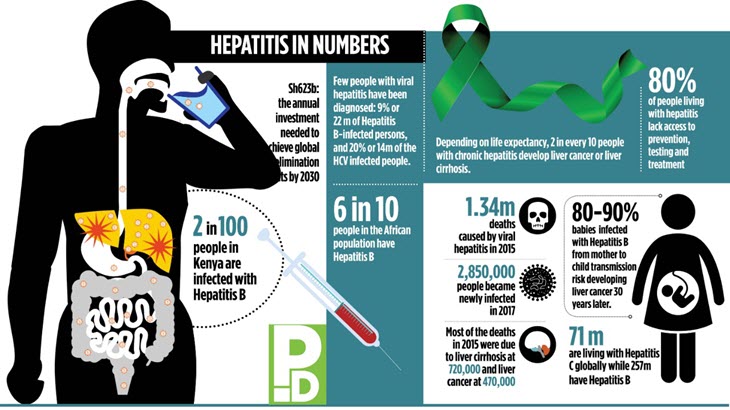

While all viruses can cause acute hepatitis, only B, C and D can progress to liver cirrhosis and liver cancer, with World Health Organisation (WHO) estimating that 71 million people globally are living with chronic viral hepatitis.

“Most cases of hepatitis A and E are transmitted through contaminated food or water. Often, these infections can be controlled and managed. They are transient and easily managed and often clear within few weeks,” says Professor Lesi Olufunmilayo, Regional Adviser Viral Hepatitis, WHO Africa.

However, few patients of Hepatitis E may develop acute liver failure, with pregnant women the most affected. Vaccines for Hepatitis A and E viruses are available with the latter only available in China at the moment.

Hepatitis B, C and D are spread through contact with blood and bodily fluids. Hepatitis D only affects people already infected with hepatitis B and is one contributing factor to liver disease. B and C infections spread through use of improperly sterilised injections, through untested donated blood, sexual contact with an infected person and from mother to child.

96 per cent

Of the five types, B and C are the most deadly, accounting for 96 per cent of all hepatitis mortality.

In the African region, for instance, Olufunmilayo says, 60 million and one million people are infected with B and C respectively.

“Research shows that poorly sterilised injections and reuse of needles in healthcare facilities as well as traditional practices such as scarification are responsible for most of hepatitis C in Africa,” she says.

In Kenya, hepatitis interventions mainly focus on Type B and C as they are potentially chronic.

“While type C is not common among the general population, it has a high prevalence among key groups including the PWIDs, men having sex with men and commercial sex workers,” says Missiani Ochwoto, Research Officer, Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI).

Illuminating study

A 2016 study found the national prevalence of Hepatitis C to be at four per cent. The Testing And Linkage To Care For Injecting Drugs Users study screened 4,032 out of the 18,000 PWIDs and found a 13 per cent and 27 per cent prevalence of Hepatitis C in Coast and Nairobi regions respectively.

The current national prevalence is estimated at 1.2 per cent.

“The figure is, however, not conclusive since it’s mainly drawn from the blood tested in transfusion centres,” says Ochwoto.

More comprehensive results of the national prevalence will be released after the conclusion of an ongoing Kenya Population based HIV Impact Assessment survey.

HBV infections are higher in Baringo, Turkana and West Pokot counties, with ongoing research showing infection is transmitted in childhood.

“This is attributed to cultural practices such as ear piercing and scarification. For that reason, hospitals in those areas and in Eldoret have reported high incidences of type B and liver cancer,” says Ochwoto.

He adds that the government is focusing on testing as one of the interventions of eliminating hepatitis in the country in line with the global commitments.

The 194 WHO member states have committed to eliminating hepatitis by 2030, cutting mortality by 65 per cent and reducing new infections by 90 per cent. If diagnosed early hepatitis is treatable.

For type C, the interventions are targeted mainly on the key populations. “For PWIDs, for instance, we have found that supplying them with safe needles and syringes and linking them to treatment reduces the incidences,” he says, adding that emphasis on proper blood screening before transfusion as an important move to curbing the spread of type C.

Treatment of hepatitis C is not only expensive but also inaccessible to many. To lower the cost, the government is in negotiations with Egypt to acquire subsidised drugs.

Ochwoto says earlier negotiations with Egypt saw the cost of Harvoni drug reduce from Sh120,000 per dose to Sh60,000.

The negotiation seeks to see the cost drop further to Sh20,000, to make it possible to roll out the drug in all health facilities and ensure more access.

Reduce burden

Patients take the drug for 12-24 weeks, and a drop in cost could see a lowered burden on patients. Unlike other Hepatitis C drugs that treat a specific genotype of the disease – namely 1,2, 3,4, 5 and 6, Harvoni is able to treat at least three of them.

“Prior to introduction of Harvoni, patients had to undergo tests to determine the genotype of the disease. This ended up increasing the overall cost of treatment as such single test costs Sh60,000,” adds Ochwoto.

As for type B infection, prevention and eradication is through vaccination. “Hepatitis B can be prevented through effective vaccination, which is at least 95 per cent effective, especially if given at birth or in early childhood.

In Africa, most transmissions of HBV happen before the age of five,” says Olufunmilayo.

In 2001, Kenya launched the Pentavalent vaccine, which protects children against five diseases including Hepatitis B. WHO recommends three doses of the drug, with the first given within 24 hours after birth, the second shot after 28 days and the third at four months.