He is the longest-serving president Kenya has ever had. As he exits the stage, Daniel Toroitich arap Moi spent about 55 years in politics.

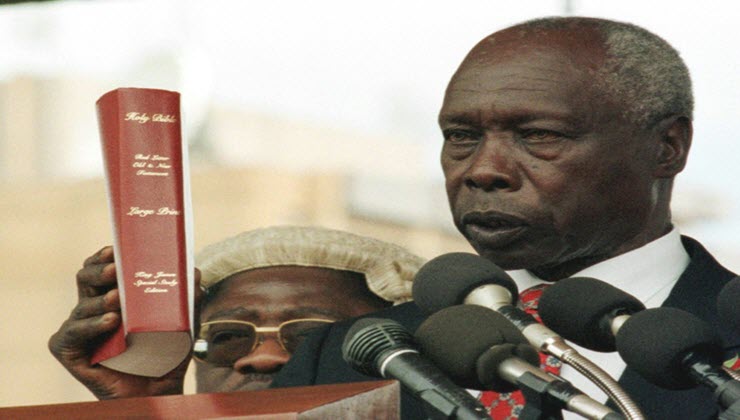

Moi, who had been serving as Kenya’s vice-president since 1967, succeeded to the presidency smoothly following the death of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta on August 22, 1978.

His presidency began well and a campaign to secure his acceptance was brilliantly masterminded by Charles Njonjo, the then attorney-general, who became a powerful ‘kingmaker’ in the process.

Among Moi’s first acts was to announce immediate elections, show his determination to tackle the endemic corruption that appeared to have become part of national life, and also worked to lessen Kikuyu political dominance.

By 1980, however, criticism of Moi’s administration from university students and the National Assembly was increasing sharply.

And despite efforts to attract his former KADU ally, Oginga Odinga, in the ranks of KANU following his sacking as vice-president by Kenyatta in 1966 for his ‘radical’ views, Oginga launched an attack on land grabbing, widening the political conflict.

The honeymoon that president Moi had enjoyed with the Kenyan people since he succeeded Kenyatta in 1978 seemed to have worn off by 1980.

On becoming president, Moi —who had joined KANU from KADU where he served as the deputy leader, quickly — adopted the popular catchphrase ‘Nyayo’ (footsteps) to show that he would follow the path laid down by Kenyatta.

Moi, a Tugen from the minority Kalenjin group, had begun his political career in 1955 when the British appointed him to the legislative council, popularly referred to then as Legco.

1989 Coup d’état attempt

But things came to a head when a section of the air force mounted a coup in Nairobi on August 1, 1982, seizing key points in the city that they held for a day until the Kenya Army and the General Service Unit regained control.

A dozen air force officers and two leaders who had fled to Tanzania were repatriated, tried and sentenced to death.

By 1983, Moi got rid of Njonjo, the ‘kingmaker of 1978’ over fears that he was growing too powerful and supposedly behind alleged machinations to replace him. After going through a commission of inquiry, Njonjo was pardoned but his public and political career was at an end.

Moi increased his grip on power by transferring the control of the civil service to his office, the power to dismiss the attorney-general and judges, and in the process weakened the independence of the Judiciary.

But by 1987, Kenya was attracting increasing criticism for its poor human rights record and even though KANU won the 1988 elections, which led to the demotion of the popular vice-president Mwai Kibaki in a post-poll reshuffle, the seed for the clamour for multiparty democracy had been planted.

Multiparty Democracy

Charles Rubia and Kenneth Matiba effectively started the debate on multiparty politics in 1990 when they applied for a permit to hold a public rally to discuss democracy.

The government had them arrested and detained without trial. Nonetheless, the government reluctantly moved towards multiparty democracy but Moi, correctly, warned that pluralism would lead to a reversal to tribalism, a national vice he sought to combat with inclusive governments.

Donors suspension of US$1 billion aid to the Moi regime in November 1991 lead him to reluctantly accept to reintroduce democratic elections, which were held the following year.

However, Moi skillfully outmaneuvered and divided the opposition which split into several parties from the Forum for Restoration of Democracy (FORD), and survived through the decade.

Moi formed Kenya’s first coalition government in June 2001 when he appointed Raila Odinga, then the leader of the National Development Party, to the Cabinet as the Minister of Energy.

The same year in November, he made Uhuru Kenyatta, son of Kenya’s founding president, the Minister of Local Government in maneuvers largely seen as political succession planning ahead of the 2002 election.

Change of Guard

Under the constitution, Moi’s rule ended in 2002 and his political machinations were aimed at breathing a new life into KANU, an effort that failed as the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) swept to power in a landslide election.

NARC won 132 seats in the National Assembly against KANU’s 68 and Kibaki, Moi’s former vice-president, won the election against Uhuru Kenyatta with 3,578,972 votes equivalent to 62.3 percent of the vote.

Moi retreated to a quiet life where he watched NARC transform the battered economy, but also watched as tribalism clawed its ugly head into national politics as he had predicted and warned.

Kenya’s worst political crisis happened in the aftermath of the 2007/8 General Election and ironically involved the same characters that Moi had warned of the dangers of multiparty politics in an ethnically diverse country.