Patrick Mwangi

Kenya needs to move blood transfusion system to the modern technology which enables collection of specific blood components directly from donors, an expert has said.

In Kenya, the practice is the whole blood donation.

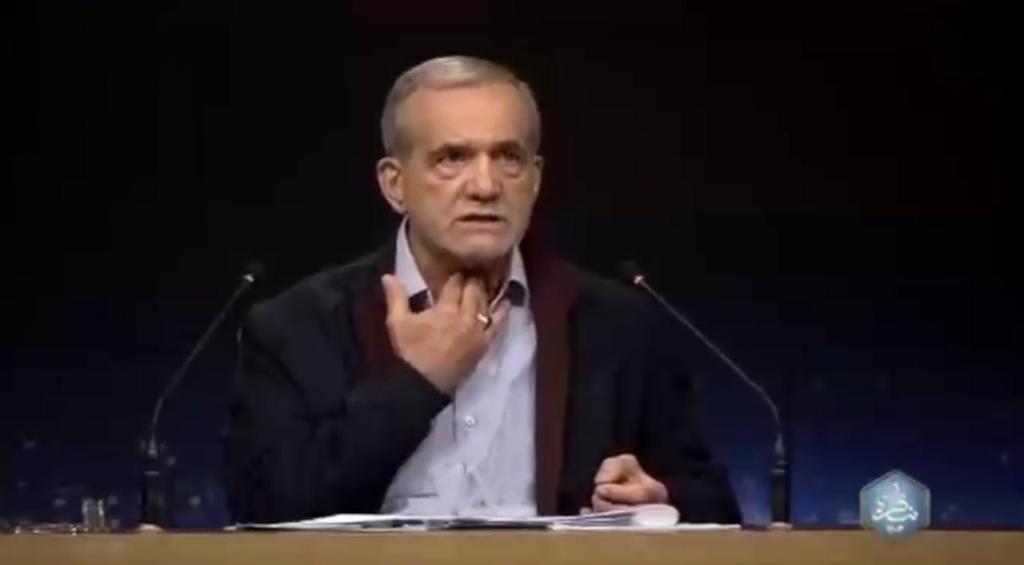

According to Dr Peter Mwamba, this is wasteful, and the modern practice globally is to give the right component for the specific indication.

Dr Mwamba, a haematologist and blood transfusion specialist at the Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH), says the modern technology used for collection of specific components, known as apheresis, is only available in two private hospitals in Nairobi and one in Mombasa.

A haematologist is a doctor specialising in treatment of blood disorders. Whole blood can only be used to treat one patient, he notes, adding that separated, the components can be used to treat four people.

“This is best achieved efficiently by using apheresis,” he says.

Dr Mwamba, who is also a senior lecturer and head of Haematology Department at the University of Nairobi’s School of Medicine, says the advantages of apheresis include enabling blood components to be stored separately as each has its own character.

He points out that platelets are stored at 22-24 degrees celsius, red cells at 2-6 degrees celsius, and fresh plasma at -18 degrees celcius.

Stored whole blood, therefore, destroys some of its components, making it useless when transfused to treat conditions which require the destroyed components.

Dr Mwamba says that since one can get two units of red cells from one donor in one sitting, it means that two patients can be treated from one donor directly. You can also collect an equivalent of six random platelets from one donor twice a week.

You would need 12 individuals in a week donating whole blood to collect the equivalent amount of platelets, says Dr Mwamba.

Transfusion costs

“The future of blood transfusion is blood components and apheresis,” he says, adding that in developed countries such as the UK and US, apheresis is used for 100 per cent of blood transfusion.

Blood transfusion is expensive. It costs Sh12,000 to process blood from donation to being ready for transfusion.

Dr Mwamba says Kenya has largely been dependent on US funding for blood transfusion services but the support has since come to an end.

The services that the American funding used to cater for include blood collection- transport, blood bags, refreshments, tents, refrigeration, personnel (nurses and lab technicians), processing of blood (separating into various components, and testing for infections.

The donor is, however, free because blood is not paid for. The other cost is the cost of transfusion into the patient and this varies from hospital to hospital.

In Kenya, donated blood is tested for Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, HIV 1 and 2, and Syphilis.

This is the minimum testing recommended by World Health Organisation (WHO). However, these are not the only infections found in blood, and Dr Mwamba says this is why it is important for testing to be done in a centralised system for quality assurance.

Rapid kits

He says the use of rapid kits, as opposed to screening in blood testing, is fraught with risks.

Rapid testing kits bring results in minutes, but the results are not sensitive because they miss out on infections that are in the window period (the span between when a person is infected and the test can give an accurate result).

More advanced tests, like NAT testing, has reduced the window period of HIV to within three days of infection. The problem, however, is the expense.

Dr Mwamba says the Kenya National Blood Transfusion Service (KNBTS) has been collecting between 150 and 180,000 pints of blood annually in the last four-five years.

WHO recommends that a country should collect blood from two per cent of its population, meaning that Kenya should be collecting at least 800,000 pints annually from its estimated 50 million people.

This means the government needs to budget at least Sh9.6 billion to collect adequate blood for the country.

In Africa, South Africa has managed to hit the WHO recommended rate, and it collects a million pints a year from its population of 56 million.

Locally, the main challenges have been the shortage of personnel and government support for blood transfusion services.

Dr Mwamba notes that the staff currently working on blood transfusion services is half of what is required.

Two years ago, he says, the other half lost their jobs after the US government cut the funding. Services, especially blood collection, have suffered as a result.

He notes that the last budget did not have a dedicated vote for blood transfusion services, which means the service remains wholly reliant on US government support, which is no longer available.

KNH collects its own blood, but it manages only 100 pints against a daily requirement of 200 pints.

“Most times we have to beg for blood from hospitals such as Mater or Nairobi Hospital,” says Dr Mwamba, adding that in most cases, only the emergency cases can get the needed transfusion. [email protected]